it’s

anarchical it’s acupunctural, well

it’s both / marco casagrande

- Anna Yudina / MONITOR #68

048

Pictured on

this spread: the construction of the RUIN ACADEMY in Taipei (Taiwan, 2010) and

the SANDWORM in Wenduine (Belgium, 2012)_PHOTO: NIKITA WU

051

Working

with illegal architecture in Taipei to save TREASURE HILL community as a source

of local knowledge, and therefore a key to environmentally sound solutions for

the city. Originally founded by construction workers together with the KMT

veterans from Mainland China, the community used to farm the entire flood plain

from their homes to the Xindian River. Every family used to have a boat. At the

time when the river has not yet been polluted, it was the bases of everyday

life – a source of domestic water, fish and seafood.

Below:

Marco Casagrande at the construction of the BUG DOME (Shenzhen, 2009), a

temporary venue for underground cultural events and a social club for builders

(more on pp 056-057).

Four weeks

to erect a willow-woven pavilion for the Beaufort Triennial of Contemporary Art

(Belgium, February). Ten days of Survival Architecture workshop to populate a

frozen mountainous lake with nomad shelters (Norway, March). A trip to Estonia:

Aalto University’s Department of Environmental Art builds connections with the

neighbouring country, its universities, artists, architects, urban planners and

“even some guys squatting in an abandoned factory” (May). It’s a Saturday

afternoon; Marco Casagrande – architect, anarchist, artist, akupunk and

partisan of real reality / is back to his home country, Finland, and ready to

share his ideas with MONITOR.

Architect

& team build a temporary bamboo shelter on a patch of land encircled by

high-rises and highways. It can serve as a social club for illegal workers from

an adjacent construction site; a concert venue for underground bands and poets;

a gathering space for the neighbourhood folks; a lounge for university

workshops…You do not even need to remove the whole thing when it’s over: in a

few months it will be overtaken by vegetation, then disintegrate on its own.

“This architecture is like an insect that undergoes a process of transformation

from egg to larva; then it cocoons and becomes a butterfly. When I design, it’s

an egg; the construction process is the larva phase; when completed, it’s a cocoon.

But I may not be able to answer what the butterfly is. Possibly, it’s the way

people feel about this building.” Casagrande is not happy with the superficial

attitude of today’s media, which banalizes architecture to a series of elegant

photos carrying no trace of the process that has shaped it and made it real. “The

construction process is like a gift. You work so hard designing and negotiating

to get it built. We have an aspiration that brings together ten people from

different countries for one month,” – Marco refers to the recently completed

Sandworm in Wenduine. “We develop our own routine, and take care of each other,

and prepare food together, and it becomes real. Then at some point architecture

overpowers us as designers or builders; we are just working for what becomes

our boss. It feels like being constantly on drugs; we sacrifice everything for

it to happen. And when it’s ready, we don’t even realize it. It’s a shock.”

To read

about architects as shamans go to page 052

To read

about business hara-kiri as an eventual door opener go to page 55

052

Working

hard to ignite the process, balancing on the borderline between control and

accident, the architect, in Marco’s view, functions as “the most sensitive

antenna that receives what an object wants to say of to be.” Like a shaman

whose senses reach beyond the visible and palpable reality, the architect

negotiates with the collective consciousness and externalizes this invisible

presence into built environments, thus making it accessible to everyone else.

“But don’t forget that shamans are not heroic figures: to protect their extreme

sensitivity, they can be disgusting and bizarre. I play many roles

simultaneously. As an architect, sometimes I have to be very business-oriented,

or very aware of how to talk to people, but inside myself I know I do it just

to smuggle into the real thing.”

Casagrande’s

Treasure Hill adventure in Taiwan is a beautiful case study in negotiating with

a whole bunch of realities. A total foreigner, he managed to turn around a complicated

issue with an illegal settlement in Taipei. “Who Cares, Wins” is a captivating

slogan, but exactly, what do you do in order to win?

In 2000, at

the Venice Architecture Biennial, architects Casagrande and Rintala presented

an old barge with 22 oaks; the trees were planted on 60 minutes’ worth of human

waste produced by the city. A flyer picked up from the Venetian ground led to

an exchange with one of the Taiwanese curators, and, later on, to Marco’s

participation in a conference in Taipei. He remembers being overwhelmed by the

picture of pollution in “thi park of a city where you had to clean up any bench

before sitting down.” How come these inherently savvy, intelligently anarchic

people had completely destroyed the river that used to be the source of the

city’s life?

“Back to

Finland, I wrote a letter to Taipei authorities, with a list of reasons why the

city was going to die. Two years later, they invited me to Taipei for three

weeks to make some alternative proposals for the future of the city. They

provided me with all kinds of data, but there was no correlation to the things

that interested me: the people and how they used to city, and nothing about

nature. It was like reading a manual for some machine; I couldn’t do anything

with it! My first proposal was to organize a Hercules airplane parachuting me

above Taipei: I wanted to spread vegetable seeds, and it was no metaphor. This

was not possible, but then one professor showed me the Treasure Hill. By the

time, the city had already bulldozed three layers of this terraced hillside

settlement. When I first came to see the place, people were hiding inside their

homes because they thought I worked for the government (which I actually did).

I was not able to talk to anybody, but I could feel it smelled like slow death:

people already knew that the city would take down their illegal settlement. I

started studying how they lived. They were very poor; they stole water and a

little bit of electricity from the city. Their wastewater was filtered through

the terraces of the jungle, so that towards the bottom of the hill it was

relatively clean again and could be used for farming. Organic waste was

transformed into compost. At the same time, these people harvested the city:

they collected garbage, recycled it and sold back. The Treasure Hill was a

parasite, and yet it stood for such ideas as urban farming or water

circulation, so I suggested legalizing it to see what could be learned from

having this organic acupuncture needle inside the industrial city.”

The

authorities preferred not to gamble their reputation: neither permission nor

prohibition, just stepping aside to watch this strange man face the Taipei

reality on his own. Would he sink or survive? Casagrande made a tour of local

universities and recruited 200 students and a few professionals to work as

section commanders. “We had no building materials, but the work force was

already there, cleaning the place, and people started stepping out of their

homes. They felt that the energy focus had shifted from destruction to

construction. I sent some beautiful girl students to a huge construction site

nearby, to ask for materials. Since then, every day at 7:30 in the morning, we

had to wait by a certain road where the trucks would briefly stop to unload a

bit of their cargo for us and move on. “Mrs Chen, then 87, the matriarch of the

Treasure Hill community, adopted Marco like a grandmother, feeding her

“grandson” with Chinese medicines to maintain his high energy level through the

difficult local climate.

Farming at the Treasure Hill; a map of urban farms and community gardens in Taipei; a sketch by Marco Casagrande mapping out the functional organization of the Treasure Hill, as well as his team’s interventions to facilitate the functioning of the community.

And suddenly

something has changed. Volunteer were coming to join Marco’s team. The same

people that had been destroying the slum a week ago started showing up to

recite poems in front of the locals and cameras. The major came from an

accidental visit and spoke of the hope the Treasure Hill held for Taipei. The

New York Times and Discovery Channel reported from the site. The city finally

wanted to legalize the Treasure Hill: with all the support Casagrande and his

fellow thinkers-and-doers were getting from every direction, the officials felt

that their own faces were no longer at risk. The delicate issue of the DIY

homes not meeting any norms of the building code has been resolved by

legalizing them as public art commissioned to a foreign artist: “We signed a paper,

and the Treasure Hill became an environmental artwork. Architecture could not

have done that.” Bingo. Casagrande, in the epicentre of this productive

anarchy, has done his work of a trickster, and it was only the beginning of his

affair with Taipei…

For nomads

and pagans as the founding force behind the post-industrial city - go to

page 061

055

This power

of architecture is best explained through the idea of weakness – in the words

of Sou Fujimoto, an order that incorporates disorder and uncertainty. WEAK! is

the name of the loosely affiliated team that unites Casagrande and his

Taiwanese colleagues Hsieh Ying-Chun and Roan Ching-Yueh – the Treasure Hill

was their first joint effort – who share the same live-and-let-live-approach

and believe in the intrinsic wisdom of reality. Which gets us very close to

Urban Acupuncture and the 3rd Generation City, the keynotes of

Casagrande’s trans-architectural philosophy.

His debut

was quite traditional; the mental image of an architect – work routines, looks,

earnings, position in the society – quite complete. After half a year of

designing what he calls normal commercial projects, Marco started to realize

“that the architect was the first to compromise – for money, for politics, for

media, for anything.” He felt that his designs were becoming “crippled mutants

of the original ideas, so maybe it was better for them to die before even being

born.” Horrified by the prospect of themselves degrading into something equally

unwholesome, Casagrande and his then partner Sami Rintala to do a project where they could be their own

clients and see what would happen. With the small money earned from designing

mutants, they built Land(e)scape (1999), three derelict barns perched atop 10-m-high

stilts, as if marching on long thing legs. Escaping towards the cities? Trying

to catch up with the farmers that had abandoned them? The performance during

which the barns were set of fire on an October night gathered an audience of

6.000. “Our decisive and dramatic business hara-kiri marked the start of

something we could not foresee: people asked us to continue this strange line

of work…As for the Urban Acupuncture, it’s a king of magic item you find if you

are able to enter the zone that is no longer bound to any particular

discipline. It’s neither architecture nor environmental art nor natural river

restoration nor anthropology.” Initiation disguised as hara-kiri, an a new

freedom that comes with it.

scape.jpg)

scape+by+Casagrande+and+Rintala.jpg)

scape.jpg)

Marco’s

first attempt at attacking the city: an installation and performancee made with

Sami Rintala, LAND(E)SCAPE (Savonlinna, 1999) commented on the desertion

of the Finnish countryside. Three

abandoned barns “were driven to the point where they have had to break their

primeval union with the soil. Desolate, they have risen on their shanks and are

swaying towards the cities of the south.”

Urban

Acupuncture is a methodology combining the theory of urban design with that of

acupuncture. In UA, an area is regarded as a complex organism in which

different “energy layers” overlap, influencing resident’s behaviour and

conduct, but also the way an urban area develops. UA is a point-by-point

manipulation of urban energy to create a sustainable town of city, which

Casagrande has dubbed “3rd Generation Cities.”

057

The UA

theory celebrates the possibility of a lightweight touch with a total impact.

UA is ruining the industrial surface of the built human environment. Ruin is

when man-made has become part of nature. A weed will root into the smallest

crack in the asphalt and eventually break the city. UA is the weed and

acupuncture point is the crack.

The first

generation city was the human settlement in straight connection with nature and

dependent on nature. The second generation city is the industrial city.

Industrialism claimed the citizens’ independence from nature – a mechanical

environment could provide humans with everything they needed. Nature was seen

as something un-necessary or hostile – it was walled away from the mechanical

reality. The Third Generation City is the organic ruin of the industrial city.

The 3G City is true when the city recognizes its local knowledge and allows

itself to be part of nature.

UA has no

fixed scale. “Acupunks” practice micro interventions like the Human Layer

projects in various European cities, but they may also come to Puerto Rico and

rethink an entire infrastructure, aiming to render the city liveable for

pedestrians, and not the car traffic alone… Casagrande claims to have

discovered UA – essentially, a method where humans are seen as part of nature –

when he recognized the city as an enemy. “I am addicted to the city, but it’s a

place where people get corrupted, where they blindfold themselves and live in

constant hypnotization. You can fly your kite, or drive a scooter, but you

don’t look inside yourself because this is called paranoia. It’s a climate that

creates pollution and prostitution, so of course I was interested: it was like

going to a whorehouse. But the city is also the ultimate place where people

meet, and the collective conscious is cooking up here. I wanted to deal with

this mass of organic collective energy, so the city became by target and UA –

my too. It’s the strategy of a bird that shits over a city, and its shit

contains a seed, and this fertilized seed goes down, and cracks the asphalt, and

this organic thing starts growing. I needed to penetrate through the industrial

surface in order to reach that what everyone sees and feels but the official

system cannot deal with. At first I believed to be alone, but there were other

people thinking along the same lines. The biggest step forward was when I found

out that normal, real citizens were breaking the official city all the time.”

Casagrande

describes the forces that act in any built environment as different layers of

editing. Taipei developers act on a macro scale, while simultaneous micro

editing happens as grandmothers cultivate their vegetables an temporarily

available wastelands pending the start of construction works. “I can say more

or less the same about Buryatia (Russia) where I have seen a plain occupied by

five-storey high radio telescopes in dialogue with the universe, and the sheep

eating grass under these huge cosmic mirrors…Or a log-house with an Internet

Café sign on it, which I spotted driving through Siberia. Inside, there was a bunch

of computers, ripped into pieces but with high speed internet…Supermachines in

an almost collapsed house in the middle of nowhere.”

058

The node

where all these layers are explored and comprehended is a corner squat in an

urban block awaiting major reconstruction. JUT Foundation for Arts &

Architecture (part of JUT Land Development Group) has transformed a cluster of

vacant buildings into temporary homes for various cultural collectives. The

Ruin Academy, an independent cross-over platform for architectural research

founded by Casagrande in Taipei, is both a prototype and think tank for a 3rd

Generation City. “All the interior walls and windows are removed in order to

grow bamboo and vegetables inside the house. Professors and students sleep and

work in mahogany-made ad-hoc dormitories and have a public sauna on the 5th

floor. The entire building is pierced with 6-inch holes to let rain inside.” It

is here that they develop city-scale “Treasure Hill” strategies, preparing the

changes – to stop the pollution, to reunite the river and the city, etc. – that

the authorities would be eager to initiate themselves were they not immobilized

by the rigidity of the official structure.

To find out

how all this could have been entrusted to an alien - go to page 061

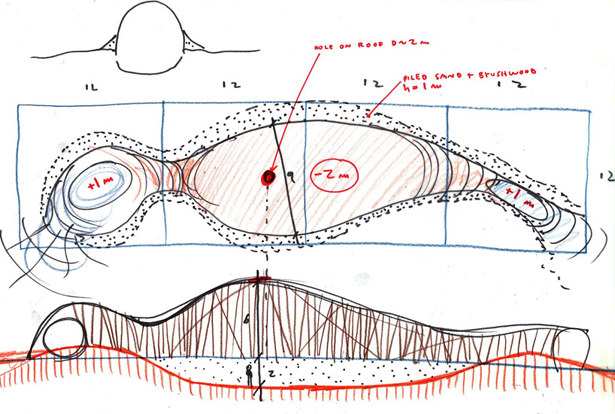

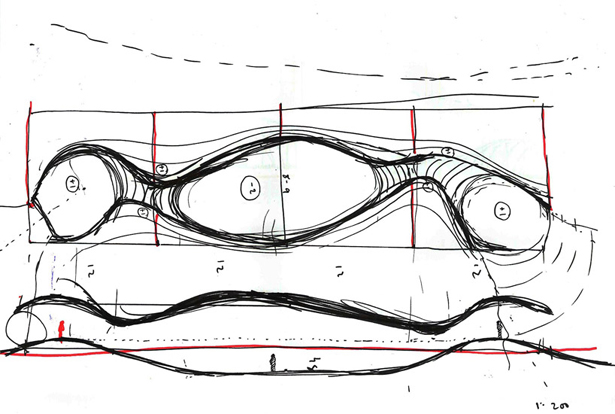

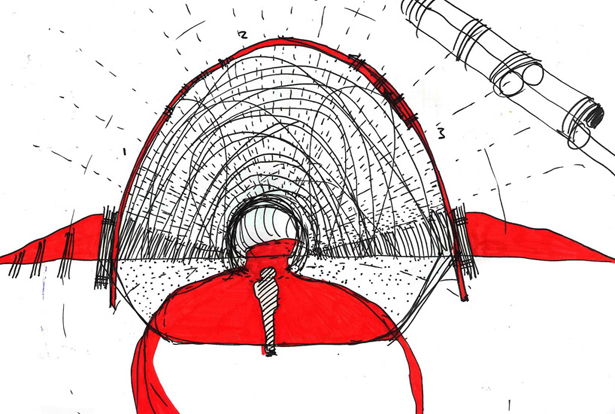

Built on

the dunes of the Wenduine coastline, the SANDWORM (Belgium, 2012) is an

“organic structure/space/creature” that unites the realms of architecture and

environmental art. The installation designed for the Beaufort 04 Triennial of

Contemporary Art measures 45 x 10 x 10 m and is constructed entirely out of

willow. In four weeks’ time, Casagrande and his team of young architects and

local willow weaving experts have built a sample of weak architecture – “a

human made structure that wishes to be part of nature through flexibility and

organic presence.” The space is intended for “picnics, relaxation and

post-industrial meditation.”

“The RUIN

ACADEMY is an experimental platform for knowledge building on the way towards

the Third Generation City – the ruin of the industrial city. The Academy offers

a public sphere for cross-disciplinary communication within the general field

of built human environment, city. We don’t focus on the different disciplines

of art and science. We focus on local knowledge, people and stories. The

Academy is more like a Pub than a University – or like a public sauna in

Finland, where everybody is stripped naked from the President to the Police,”

says Casagrande in the Anarchist Gardener, a newspaper published by the

Academy. “The Ruin Academy is and independent and free platform where the

different student groups and other players can meet. The Academy (…) is a

simultaneous construction site and a ruin. We don’t know what we will find but

the first step is to break the box, ruin the city. What comes to the academic

control, we will give up in order to let nature step into our ruin. There is no

other discipline than nature.”

No way to

approach Marco with a conventional West-meets-East attitude. Both the compass

and the humanity can offer more than these two dimensions. For instance, the

Non-Urbanized Nordic Barbarian who “arrives to the city, breaks it, and in the

end becomes a citizen.” But (not so) deep inside this citizen-barbarian retains

his nomad mentality that makes him just the right guy to go acupuncture Taipei,

which is a nomad camp, too. Its inhabitants are already beyond the “industrial”

view of a city as something fixed and permanent. The nomadic quality of Asian

cities makes it much easier for Casagrande to work in Taipei than in Western

Europe.

Probably,

another link between “Easterners” and “Northerners” is their understanding of

relations between architecture, people and nature. They are aware that people

cannot dominate nature but only coexist with it. Northern Europe, formerly a

rural region characterized by late industrialization, has in a certain way

skipped from pre-industrial directly into the post-industrial phase. Take the

Finns, who, according to Marco, live in a quantum reality. “Whenever possible,

the guys who design Nokia escape from the city to their cottage, where they

stay in primitive, almost caveman-style conditions. In a wooden cottage,

ideally built by yourself or at least by someone of your ancestors, you can

stay naked, go to the sauna, fish, hunt, get drunk; your children are running

around, and you feel connected to eternity. And this reality of hyper modernism

intermingled with primitivism is true not only for Finland. There are places

like Taipei where, instead of a summer cottage or a rowing boat, you have an

anarchist grandmother who breaks the structure of the city and steals water

from the official water supply. And, because Asian mentality respects the

grandmother, everyone feels that what she does is good for them. They escape to

her urban farm or collective garden to get back to the primitive, and it’s

caveman style, too, even though skyscrapers stand a mere 10-20 m from there.

This negotiation between the skyscraper and the anarchist grandmother can

create new knowledge. UA is not about providing a solution; it’s more like this

quantum existence within parallel realities.”

Places,

too, can toggle between different realities and live several lives during the

day. A downtown street on office hours, after dark it turns into an illegal

night market. Cars move away, replaced by guys with trolleys selling fried

squid, strawberries in caramel, fake-label clothes and everything else. “These

urban nomads seem to come from nowhere. They have their own hierarchies and

structures, and I guess that the people who buy these strawberries are the very

same office guys who live in a completely different reality in the daytime. And

then the morning comes, and the street is cleaned up to give way to the

official city. Nomad venders take good care of their surroundings, and everyone

follows the rules. Police cars that patrol the street give enough time for the

nomad alarm system to alert venders. They disappear some 30 m away so that the

patrol can drive through the street with their digital camera on – and come back

as soon as the policemen are gone. In a city, this pulsating mess acts as

compost, an organic material you stir every now and then.”

The RUIN ACADEMY floor plan:

GROUND FLOOR - entrance, event space

1st FLOOR - student dormitory

2nd FLOOR - professor's deck

3rd FLOOR - lounge

4th FLOOR - sauna, actually

064

The CHEN

HOUSE (Taiwan, 2008) – a farmhouse that Marco Casagrande has constructed

together with architect Frank Chen for Chen’s retired parents. The structure in

tropical hardwood, with concrete used for the foundation, cost less than the

basic interior decorations of an average Taipei apartment. An example of

bioclimatic architecture meant to coexist with nature, the building is

optimized for the complex of local conditions: recurring typhoons, floods and

heat. When a typhoon strikes, winds blow through a short walkway between the

main and side rooms, leaving the internal spaces intact. The same walkway, but

also the intentional gaps all over the building walls, allow the cool air to

ventilate the rooms, maintaining comfort during the hottest periods.

PHOTO: ADDA ZEI

Casagrande esteems favelas and slums as high-potential acupuncture points. “Industrialism and any other kind of human control introduces rigidity – and, like with anything else in nature, rigidity means death. Flexibility, mobility, softness, weakness have a sense of life to them, so the problem itself may contain a better solution than the attempt at total control,” says Marco who reveres Russian writers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Their social science fiction deals exclusively with problems that have no satisfactory solution on the material plane. They pose the kind of question where every answer is strictly personal, one-off, and valid only if you find it deep inside yourself. Problem-solving is different from improvising. Casagrande opts for improvisation.

scape.jpg)

scape+by+Casagrande+and+Rintala.jpg)

scape.jpg)