What is the Third Infoscape?

How can we grasp the potential revolutionary character of our daily lives, educate our gaze to capture unforeseen opportunities and experience our cities as living beings, to which we all participate and onto which we can all contribute to transformation and change?

The ideas of Microhistory, of Third Space, of Third Landscape, of Third Generation City and of Urban Acupuncture will help us to try to give answers to these questions.

Let’s start from History.

History

When we study

History, we tend to imagine studying

“large history”. The history of the great people and great events/trends which transformed the course of time, wars, societal transformations. Changes which happened on a large scale, treaties, alliances and agreements which shaped the lives of entire populations.

This is, of course, not the only way in which we can research and study history. The term “History” itself is an umbrella term enclosing a rich variety of different approaches.

Among them is the really interesting possibility to study

Microhistory,

“the intensive historical investigation of a well defined smaller unit of research (most often a single event, the community of a village, a family or a person)”

This might seem somewhat less relevant than history, as it could resemble an effort to focus on things which are of smaller importance, almost case studies that would, then, need to be framed into a wider context to be significant.

But if we think about it, this might well not be the case.

History is, of course, the result of the progression of large-scale transformations to the structures of human societies, their relationships, their disputes and agreements.

But these large changes do not happen in a vacuum. They happen within human societies, which are made of human beings, and by their relationships, cultures, imaginations, desires and expectations.

So it is possible and valuable to view the study of History also as the possibility to “ask large questions in small places or contexts”, as hypothesised by Charles Joyner [1].

To try to explore the conditions in which these large scale events and transformations actually took place, through people and the mutation of their daily lives, of their cultures and desires.

And that’s precisely what happened when historians started to understand that

certain “political events and social realities” could not be explained adequately by existing macro-historical models, as highlighted, for example, by

Giovanni Levi [2].

In essence, historical histories did not account for the experiences of all members of the event, society, or culture being studied. As a result, microhistorians have made a point of viewing people not as a group, but rather as “individuals who must not be lost either within the historical processes or in anonymous crowds”. [3]

Microhistorians have attempted to formulate a history of everyday life. [4]

Everyday Life

In his “The Practice of Everyday Life” [5] Michel De Certeau transformed the study of “everyday life”, shifting it away from the study of popular cultures and from the research about the social and political struggles which happen with the daily forms of resistance to the regimes of power, in an attempt to outline the way individuals unconsciously navigate everything, from city streets to literary texts.

This approach leads to an interesting distinction among the strategies and the tactics.

The idea of strategies is linked to the one of institutions and to the structures of power, describing and producing the prescriptions (the codes) according to which the elements of reality should be interpreted. They are the official rules of society: the laws and regulations, the official usages of objects and spaces of the city. They are enacted by encoding, by putting objects and places on maps with precise legends (or codes), or by establishing boundaries and borders.

On the other side are the tactics, referring to people and the ways in which theycontinuously surf the strategies in unexpected ways, they navigate them according to their cultures, desires, urgencies and imaginations. People constantly perform the environment producing their own interpretations of reality, using objects and moving through cities in ways that are tactical and never fully determined by the plans of organizing bodies.

People fundamentally and continuously break the codes established by the strategies, enacting their tactics and, thus, re-programming the environment, and adding new codes onto it, established by acts of “making” and of “performing”, by unpredictably changing their trajectories while moving through urban space, by changing the way in which they use a certain object, and by mutating the way in which a certain space is used.

In the chapter “Walking in the City” De Certeau writes:

The ordinary practitioners of the city live “down below”, below the thresholds at which visibility begins. They walk – an elementary form of this experience of the city; They are walkers, Wandersmänner, whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban “text” they write without being able to read it. These practitioners make use of spaces that cannot be seen; their knowledge of them is as blind as that of lovers in each other’s arms. The paths that correspond in this interweaving, unrecognized poems in which each body is an element signed by many others, elude legibility. It is as though the practices organizing a bustling city were characterized by their blindness. The networks of these moving, intersecting writings compose a manifold story that has neither author nor spectator, shaped out of fragments of trajectories and alterations of spaces: in relation to representations, it remains daily and indefinitely other.

And, later:

Their story begins on ground level, with footsteps. They are myriad, but do not compose a series. They cannot be counted because each unit has a qualitative character: a style of tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation. Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their interwined paths give their shape to spaces. They weave places together. In that respect, pedestrian movements form one of those “real systems whose existence in fact makes up the city”. They are not localized; it is rather that they spatialize. They are no more inserted whithin a container than those Chinese characters speakers sketch out on their hands with their fingertips.

According to these idea, strategies and tactics each produce distinguishable parts of the city. The first is top-down and is relatively static, relating to the institutionalised, bureaucratic, legal and administrative codes which describe the spaces of the city. The second is bottom-up, emergent, dissonant, in real-time, describing the desire and visions of the city-practitioners (the performers), written on the cities through their bodies and their actions within the city.

The first represents a top-down form of information and knowledge. The second is bottom up.

The first is mainly static, and highly readable through the apparatus of signage, visual encoding and images produced by administrations.

The second one is dynamic, everchanging, multiple, polyphonic, and is below the threshold of readability as it is drawn through the bodies of city-dwellers, and is ephemeral, lasting only a few instants.

According to De Certeau, this form unpredictable creativity describes a space, in which revolutionary potentials exist, in which individuals individualize culture, and turn elements of the popular in their own, reappropriating them.

This

new space can be materialized, under the form of what geographer and urban planner

Edward Soja calls the

Third Space.[6]

According to Soja in the Third Space:

everything comes together… subjectivity and objectivity, the abstract and the concrete, the real and the imagined, the knowable and the unimaginable, the repetitive and the differential, structure and agency, mind and body, consciousness and the unconscious, the disciplined and the transdisciplinary, everyday life and unending history.

Third Space is a radically inclusive concept, in which the strategies exist together with the tactics which, thus, gain visibility and perceivability, enabling the contestation and re-negotiation of boundaries and cultural identities.

This is a process which is very similar to

Homi K. Bhabha‘s theory of cultural hybridization, in which

“all forms of culture are continually in a process of hybridity,” that

“displaces the histories that constitute it, and sets up new structures of authority, new political initiatives… The process of cultural hybridity gives rise to something different, something new and unrecognizable, a new area of negotiation of meaning and representation.”

Thus, it is a space for open opportunity, in which possibility exists according to, in turn,the possibility to recognize (to see) it in the “other”, in the tactics that are expressed in space. Opportunity exists if our gaze can become educated to see the tactics and to learn to negotiate their meaning.

The Third Landscape

When Gilles Clément described the Third Landscape he described it as [8]:

The Third Landscape – an undetermined fragment of the Plantary Garden -designates the sum of the space left over by man to landscape evolution – to nature alone. Included in this category are left behind (délaissé) urban or rural sites, transitional spaces, neglected land (friches), swamps, moors, peat bogs, but also roadsides, shores, railroad embankments, etc. To these unattended areas can be added space set aside , reserves in themselves: inaccessible places, mountain summits, non-cultivatable areas, deserts; institutional reserves: national parks, regional parks, nature reserves.

Compared to the territories submitted to the control and exploitation by man, the Third Landscape forms a privileged area of receptivity to biological diversity. Cities, farms and forestry holdings, sites devoted to industry, tourism, human activity, areas of control and decision permit diversity and, at times, totally exclude it. The variety of species in a field, cultivated land, or managed forest is low in comparison to that of a neighbouring « unattended » space..

The Third Landscape is the part of the natural environment that grows in-between bricks and stones, it is the grass that lives between train tracks, it is the natural space that finds its life in the cracks of the walls, or in the places of our cities to which we don’t pay muchattention.

It is the natural space of our cities which has not yet been encoded. It is not found in the flowerbeds and hedges which our city administrations define through borders and limits: please keep off the grass, this is a bureaucratically instituted flowerbed.

From an ecological point of view, the larger part of the biodiversity in our cities is found in the Third Landscape [9].

From this point of view, the Third Landscape can be considered as the genetic reservoir of the planet, the space of the future…..

Gilles Clément’s “Planetary Garden” is one of the most suggestive answers to the mutation of the definition of urban space. Planetary Garden is to economic and urban globalization what urban gardens were to the cities of the 19th Century: the latter represented the closed or tightly schemed design of urban architecture and layout, while the former represents the connective, fluid, mutating texture of the globally interconnected city. The Planetary Garden is the garden of the global city.

The third landscape is a connective fabric composed of residual spaces that tend to take a liquid state, never preserving shape, resisting governance. Classical preservation or environmental conservation tools such as surveillance, protection and the creation of limits and borders cannot apply to the Third Landscape without destroying its characteristics, as Clément writes [10] “not property, but space for the future”. An idea of space that goes beyond the ideas of landscape as a place for identity, being used as an asset for local societies, and as a strategic tool for memory.

An idea of space that exemplifies the possibilities of the contemporary world: a multiplication of narratives; the holistic perception of ecosystems; the possibilities and richness offered by disseminated, interstitial, emergent, mutating, temporary, polyphonic environments; the end of dualistic approaches.

As

John Barrell spoke about “

the dark side of the landscape” [11] while pointing out the imposition of a point of view of a single social class, with Clément we could speak about a “

light side”, for

the Third Landscape is not an exclusive model but an inclusive one:

“a shared fragment of a collective consciousness”.

It is based on a planetary remix (brassage) which is at the origin of the current richness of ecosystems. [12] These dynamically mutating spaces embody the presence of multiple agencies forming the city from points of view that are architectural, political, economic, poetic, activist, industrial: new forms of nature that emerge by instantaneously creatinginterstitial ecosystems that flow with the story of the city, describing a realtime syncretic map that develops together with the creation of new areas for residences, industry, commerce, business, culture and entertainment, and with the death, abandonment and decay of the previous ones, as a geography of the mutation of the city. [13]

Clément talks about the necessity of training our gaze into recognizing and understanding the Third Landscape. This requires a new possibility for vision and knowledge dissemination in urban natural environments, a renewed sense of aesthetics, and a morphed sensibility for the possibilities for interaction and communication offered by our surroundings.

This is a potentially revolutionary point of view, as it alludes to the possibility to achieve the perception of these emergences, and the possibility to transform them into a form of shared knowledge.

A similar discourse could be imagined for the Third Space: what if the emergent history of tactics could become a source of shared knowledge? What if the progressivesedimentation of this knowledge, its continuous formation of everchanging and evolving ruins, layer after layer, could become accessible and readable, through sensibility andsenseability, and through a novel form of aesthetics to stimulate both perception (attention) and awareness, to describe the progressive history of daily life: a stratified, accessible, perceivable, usable, continuously evolving micro-history?

The Third Generation City and Urban Acupuncture

What is a ruin?

A ruin is the progressive reunification of objects and architectures to nature. As buildings grow older, the action of natural agents, of human beings and of the Third Landscape mutate them, bringing them into a different form: more organic, and systematically integrated into the natural environment.

In a way, nature and human beings ruin buildings, transforming them into ruins.

From a different point of view, the actions of human beings and nature bring buildings into a different state, transforming them into ruins, providing evidence of the history of humans’ and nature’s interventions on architectures, of the patterns according to which they have been used daily. From this point of view, ruins expose the history of the natural (and human, as integrated in nature) environment and of its daily life.

Ruins are, to all effect, a history and a source of knowledge and of information, enacted through the layering processes of the results of the actions of human beings and of natural agents.

From Marco Casagrande‘s definition [14]:

Third Generation City is the organic ruin of the industrial city.

Third Generation City is true when the city recognizes its local knowledge and allows itself to be part of nature.And [15]:

The Third Generation City is the industrial city ruined by the people – human nature as part of nature.

Like a weed creeping into an air-conditioning machine the industrial city will be ruined by rumors and by stories. The common subconscious will surface to the street level and architecture will start constructing for the stories – for the urban narrative. This will be soft, organic and as an open source based media, the copyrights will be violated. The author will no longer be an architect or an urban planner, but somehow a bigger mind of people. In this sense the architects will be like design shamans merely interpreting what the bigger nature of the shared mind is transmitting.

This last definition is specifically interesting for all our discussion: the image of the layering of the subconscious, of the stories and narratives produced by people emerges as a novel (un)building material which is capable of preserving history and knowledge, by transforming spaces, whose authors will no longer be architects or planners, but people themselves.

The third generation city is envisaged to be an organic layer that promotes alternative modes of living as well as narratives, or “urban rumors”

The Third Generation City as a form of knowledge.

And, as in the Third Landscape, the need to educate our gaze to recognize this kind of stratification as a new kind of aesthetics, as a new form of perception for possibility and opportunity: an open space for the future.

Thus it is imaginable to acknowledge this process and, thus, to imagine the city as a whole, as a body, which includes both architecures and their emergent layering with the history and knowledge of the daily lives of human beings and nature.

This body would not be static, with continuous, emergent flows of knowledge and information taking place throughout it.

Thus enabling the visions of architect

Vilen Künnapu‘s theory of energy center architecture aiming in tuning the urban condition into a network of spiritual layers, and architect

Marco Casagrande‘s theory or

urban acupuncture in which the cities are treated punctually as energy organism towards an environmentally (and socially) sustainable development.

According to Urban Acupuncture, small scale interventions can be used to transform larger urban contexts. From this point of view, the sites of the interventions can be selected much in the same ways in which traditional Chinese Acupuncture selects the points in which to insert the needles: locations which are fundamental for the flows of information, communication and knowledge in the city.

City is viewed as multi-dimensional sensitive energy-organism, a living environment. Urban acupuncture aims into a touch with this nature and Sensitivity to understand the energy flows of the collective chi beneath the visual city and reacting on the hot-spots of this chi. [16]

Urban Acupuncture is connected with the perception of the city as a body, withnarratives, emotions, information and knowledge as its main meridians for energy flows.

Urban acupuncture bears some similarities to the new urbanist concept of Tactical Urbanism. The idea focuses on local resources rather than capital-intensive municipal programs and promotes the idea of citizens installing and caring for interventions. These small changes, proponents claim, will boost community morale and catalyze revitalization.[17]

The info-body of the City: the Third Infoscape

As we have seen so far, the idea of Microhistory allows us to focus onto the personal stories of people, describing territories not only in terms of the large-scale events and trends which happen in (or to) them, but allowing for a multitude of points of view emerge, the histories of the daily lives of people, which can be observed to make sense of the larger phenomena.

These stories form the Tactics, described by De Certeau, which, together with the strategies, encompass the dialectic confrontation between the top-down and bottom-up encodings of cities. The first ones are static and prescriptive, establishing strict codes and boundaries. The second ones are dynamic and emergent, and describe the performative practices of city dwellers, in their reinterpretation and reappropriation of the spaces of the city. This is the Third Space, as described by Soja.

In a parallel with Clément’s Third Landscape, we have seen the ways in which the Third Space can be used as the space for emergent opportunity in the city, an inclusive, possibilistic and accessible open space in which it is possible to define new, emergent codes, at multiple levels and according to different directions. To do this, new forms of aesthetics and perceptions must be achieved, to be able to perceive the Third Space/Third Landscape, to see and interpret it as the open space for opportunity and for a possibilistic description of the future.

With the Third Generation City, we have seen how to integrate all these levels using the idea of the ruins, in which Tactics stratify on top of Strategies, transforming them. This layering represents the effects of nature and of human daily lives on the spaces described by the strategies, their histories and narratives.

This, in turn, describes the city as a body, in perpetual dynamic evolution, in which this emergent process describes the flows of expression, emotions, information and knowledge: the energies of the city.

On these flows, in ways which are similar to the ones we find in acupuncture, we can imagine to apply Urban Acupuncture, acting on the nodes of the meridians of these flows to liberate and enhance them and, thus, producing larger effects through small interventions.

All of this process we have just described relies, as we said, on the energies of the city which are represented by expression, emotion, information and knowledge, and on their possibility to flow freely, and to leave evidence of their (micro)history to be transformed into accessible forms of awareness, wisdom, insights, enlightenment and performance.

In current times, much of these energies assume digital forms.

We have learned to use mobile devices, ubiquitous technologies, social networks and other ubiquitous forms of communication to work, collaborate, make decisions, express our feelings, learn, communicate, establish relationships, and consume. [18] [19] [20]

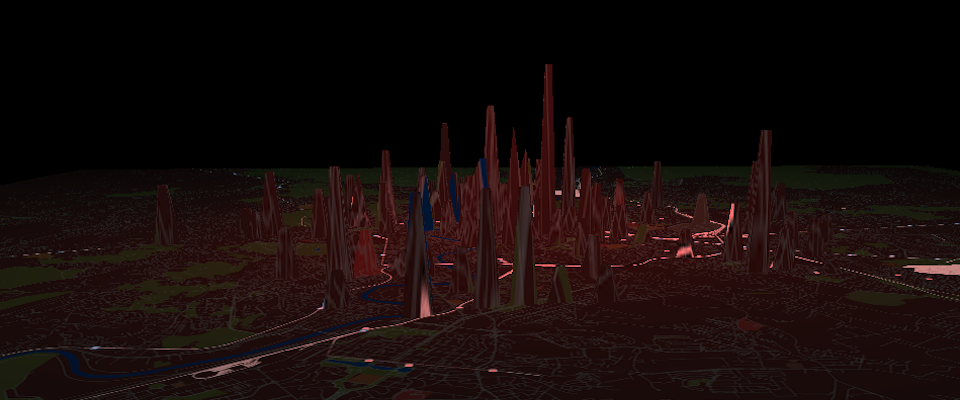

It is, thus, possible to define, along the lines of the previous definitions, a (First, Second and) Third Infoscape. Where the First Infoscape would refer to the information and knowledge generated within nature; the Second Infoscape would refer to the information and knowledge generated in the industrial city (the second generation city, the city of infrastructures, of transactions, of sensors…); and the Third Infoscape would refer to the information and knowledge generated through microhistory, through the progressive, emergent and polyphonic sedimentation onto the city of the expressions of the daily lives of city-practitioners.

By making a parallel with the previous theoretical approaches it would be, then, possible tofocus our attention onto the Third Infoscape, together with the First and the Second, to create a novel kind of sensibility, perception and awareness. And with this new form of sensibility it would be imaginable to form new modalities for observing and understanding our cities, and to perform new kinds of Urban Acupuncture interventions, based on the energy flows of the city, expressed through the digital domains which are now a fundamental part of our daily experience, inseparable from the physical one.

To achieve this, we would need to form a new aesthetic (referring to the concept of perception) sensibility, to see the Third Infoscape, and to recognize it as an inclusive space for opportunity, in the same sense pointed out by Clément when dealing with the Third Landscape.

These, among many others, are the topics which we are exploring with the

Human Ecosystems project.

Human Ecosystems

[1] Joyner, C. W. Shared Traditions: Southern History and Folk Culture, (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1999), p. 1

[2] Levi, Giovanni. ”On Microhistory.” In Peter Burke, ed., New Perspectives on Historical Writing. University Park: Pennsylvania State Press, 1991.

[3] Iggers, George. ”From Macro-to Microhistory: The History of Everyday Life.” In Historiography of the 20th Century. Hanover, N.H.: Wesleyan University Press, published by University Press of New England, 1997.

[6] Soja, Edward W. Thirdspace. Malden (Mass.): Blackwell, 1996. Print. p. 57.

[7] Rutherford, Jonathan. “The Third Space. Interview with Homi Bhabha.” Identity: Community, Culture, Difference. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1998. Print. P. 211

[9] Clément, Gilles. Manifesto del terzo paesaggio. Macerata: Quodlibet, 2005.

[10] Gilles Clément. Le jardin planétaire. Reconcilier l’homme et la nature, Albin MIchel, Paris 1999.

[11] Barrell, John. The dark side of the landscape: the rural poor in English painting, 1730-1840, Cambridge University Press, New York 1980.

[12] di Campli, Antonio. Review of the “Manifesto del terzo paesaggio”, architettura.it, 2005

[16] ”Urban Acupuncture: Revivifying Our Cities Through Targeted Renewal,” – Kyle Miller, MSIS 9/2011

[18] Salvatore Iaconesi, Oriana Persico. The Co-Creation of the City in ECLAP 2012 Conference on Information Technologies for Performing Arts, Media Access and Entertainment, pp.62.

[20] Salvatore Iaconesi, Oriana Persico. 2012. ConnectiCity: Real-Time Observation and Interaction for Cities Using Information Harvested from Social Networks, in International Journal of Art, Culture and Design Technologies (IJACDT), Vol.2, Issue 2, pp. 14–29.